ZRS-4 was delivered to Lakehurst 22 OCT 31 and was commissioned USS Akron on the 27th, with LDCR Charles Rosendahl as Captain. She joined the ZR-3 for a flight, seen here over Washington on 2 NOV 31, the single day in history two helium-lifted rigid airships would be aloft at once. In January 1932 Akron’s first Fleet exercise was structured for her to find a destroyer at sea. Not finding it sadly demonstrated the painful truth that the larger and more expensive helium-filled dirigible was little better than a WWI Zeppelin for eyeball-only searches.

ZRS-4 was delivered to Lakehurst 22 OCT 31 and was commissioned USS Akron on the 27th, with LDCR Charles Rosendahl as Captain. She joined the ZR-3 for a flight, seen here over Washington on 2 NOV 31, the single day in history two helium-lifted rigid airships would be aloft at once. In January 1932 Akron’s first Fleet exercise was structured for her to find a destroyer at sea. Not finding it sadly demonstrated the painful truth that the larger and more expensive helium-filled dirigible was little better than a WWI Zeppelin for eyeball-only searches.

The oiler-turned “airship tender” USS Patoka had its mast extended for the larger ship and this had been tested with the Los Angeles. Now it was time for Patoka’s raison d’etre, and it came off Hampton Roads, Virginia. On the 17th of January, after an initial breakaway, Akron successfully moored to the floating mast. The exercise proved the system worked; indeed, it would save Akron with replenishment on the west coast. There was no question this operation required a sheltered body of water and a full watch crew to “fly” the airship, to prevent the massive tail from dipping into the water.

The oiler-turned “airship tender” USS Patoka had its mast extended for the larger ship and this had been tested with the Los Angeles. Now it was time for Patoka’s raison d’etre, and it came off Hampton Roads, Virginia. On the 17th of January, after an initial breakaway, Akron successfully moored to the floating mast. The exercise proved the system worked; indeed, it would save Akron with replenishment on the west coast. There was no question this operation required a sheltered body of water and a full watch crew to “fly” the airship, to prevent the massive tail from dipping into the water.

Without warning, an Oklahoma Democrat up for re-election, Representative James McClintic of the Committee on Naval Affairs, instigated an investigation of what he declared to be the “Akron’s military worthlessness.” For reasons unknown he drummed up recurring sour press badmouthing the airship’s expense and build quality. Taking advantage of the general ignorance of helium’s limitations, McClintic asked why, for example, had Akron not flown to 20,000 feet as “el cheapo” Zeppelins had in the Great War?

In response, RADM Moffett offered a Congressional delegation an inspection flight. It was to take place on the 200th anniversary of George Washington’s birthday. Both rigids were to be rolled out for flight, but arriving that morning, Rosendahl insisted the equipment be switched over to roll out Akron first. There was an embarrassing delay; rather than keep the politicians waiting for cross-hangar winds to subside, Akron was instead hurriedly undocked. Worse, she’d been docked backwards from the  normal heading. The winds started listing Akron six degrees or more, trying to lift the tail off the massive stern beam. Barely clear of the door, her stern broke loose with a loud snap. Rosendahl swung aboard and shouted for the OOD to drop aft ballast, but doing so did not overcome the momentum in time. A newsreel camera captured her helpless weathervaning as the lower fin smashed and twisted into the ground. A bit more damage was incurred trying to again realign her with the hangar and get her re-docked.

normal heading. The winds started listing Akron six degrees or more, trying to lift the tail off the massive stern beam. Barely clear of the door, her stern broke loose with a loud snap. Rosendahl swung aboard and shouted for the OOD to drop aft ballast, but doing so did not overcome the momentum in time. A newsreel camera captured her helpless weathervaning as the lower fin smashed and twisted into the ground. A bit more damage was incurred trying to again realign her with the hangar and get her re-docked.

A team from Akron came out to help the Lakehurst O & R department and the crew remove and repair the lower fin. While some structure could be straightened, entire sections were rebuilt with new girders. Cable tensioners were again employed to set and adjust the lattice of reinforcing wires. Damage to the main and intermediate rings was thankfully minimal, confined to where the stern beam’s bracing wire fittings were yanked out.

A team from Akron came out to help the Lakehurst O & R department and the crew remove and repair the lower fin. While some structure could be straightened, entire sections were rebuilt with new girders. Cable tensioners were again employed to set and adjust the lattice of reinforcing wires. Damage to the main and intermediate rings was thankfully minimal, confined to where the stern beam’s bracing wire fittings were yanked out.

The two month hangar-bound fin repair period allowed the opportunity to cannibalize the ZR-3 for the parts need to finish Akron’s trapeze. Finally, the Akron was airworthy again and on May 3rd, three N2Y-1s were flown out and took turns hooking on and dropping off (right) with a fourth airplane carrying a motion picture cameraman.  Finally, the larger, heavier, more powerful XF9C-1 performed a hook-on and was hauled inside the hangar bay. Since the Fleet was next going to practice in the Pacific, on May 8th Akron began a flight to the west coast, taking the XF9C-1 and an N2Y-1 along. While the Fleet transited the Panama Canal, Akron was forbidden to fly south and transit at lower elevations. The ship encountered various weather challenges, but navigated the tricky mountain pass near Van Horn, Texas, bumping pressure height, without incident.

Finally, the larger, heavier, more powerful XF9C-1 performed a hook-on and was hauled inside the hangar bay. Since the Fleet was next going to practice in the Pacific, on May 8th Akron began a flight to the west coast, taking the XF9C-1 and an N2Y-1 along. While the Fleet transited the Panama Canal, Akron was forbidden to fly south and transit at lower elevations. The ship encountered various weather challenges, but navigated the tricky mountain pass near Van Horn, Texas, bumping pressure height, without incident.

Approaching Akron’s first California mooring, Rosendahl discharged his two airplanes to land on their own even as the morning sun began expanding the helium cells. On the first pass, untrained recruits simply gawked at mighty Akron’s passing, instead of grabbing its lines. CPOs shouted at them to grab and hold it the next time. The second attempt seemed at first successful; the mooring cable was connected. Winching in, someone aboard suddenly dropped five tons of water ballast back aft. Rising uncontrollably, the bow cable was ordered chopped. The command to drop lines was not heard back aft (photo) where recruits were obeying their emphatic last orders to hang on to the lines. As newsreel cameras filmed the black comedy of errors, sailors were injured dropping off the rising tail lines until three men were too high to let go.

Rosendahl vented as much helium as he dared, but since the lifting gas couldn’t be had in San Diego, the decision came down to the helium – or the men. Newsreel cameras recorded the horrifying drama as Harold Edsal, and then Nigel Henton, lost their grip and plummeted flailing into the dusty ground. More than the shocking tragedy to the men’s families and the piling of more bad press for the Akron, this disaster gave our civilization something sickeningly new: “The airship that cannot land.” The shocking footage since included in most every documentary, the seeming deadly uncontrolability of mandatory-helium LTA was repeatedly reinforced as Hollywood, and even TV, repeatedly recreated the drama, slamming home the harsh realities of helium operations.

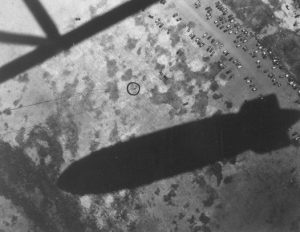

Though also untrained, sailor Bud Cowart (circle) wisely balanced his weight by standing on a pull toggle and wrapping himself with adjacent “spider” leads. Hard to access once let go, handlers nonetheless eventually managed to haul the line and Cowart aboard. With the evening cool down, the ship was finally secured to the mast. Putting most of her sailors on ground transportation and proceeding with a skeleton crew, Akron later masted to the tender USS Patoka in San Francisco bay and was replenished with what helium was available aboard.

Though also untrained, sailor Bud Cowart (circle) wisely balanced his weight by standing on a pull toggle and wrapping himself with adjacent “spider” leads. Hard to access once let go, handlers nonetheless eventually managed to haul the line and Cowart aboard. With the evening cool down, the ship was finally secured to the mast. Putting most of her sailors on ground transportation and proceeding with a skeleton crew, Akron later masted to the tender USS Patoka in San Francisco bay and was replenished with what helium was available aboard.

Moorings were made at a temporary stub mast at Sunnyvale-Mountain View (right, its hangar was then under construction.) Thousands came to see her, from San Francisco Mayor Rossi on down to a young boy named Don Venton, who would be so inspired as to become a WWII blimp pilot. Akron was flown as far north as Washington State, where folks had not seen a rigid since the ZR-1’s rim-of-America flight. Fleet exercises in June were more successful, with Akron scouting for “Green Force” and finding the “White Force” early in the morning of the second day. Yet again, the two airplanes had been left ashore. No “flying carrier,” she was just a dirigible with a declined airplane option.

Moorings were made at a temporary stub mast at Sunnyvale-Mountain View (right, its hangar was then under construction.) Thousands came to see her, from San Francisco Mayor Rossi on down to a young boy named Don Venton, who would be so inspired as to become a WWII blimp pilot. Akron was flown as far north as Washington State, where folks had not seen a rigid since the ZR-1’s rim-of-America flight. Fleet exercises in June were more successful, with Akron scouting for “Green Force” and finding the “White Force” early in the morning of the second day. Yet again, the two airplanes had been left ashore. No “flying carrier,” she was just a dirigible with a declined airplane option.

Images of the Akron when in California show a rather soiled appearance, with the soot from the engine exhausts presenting a cleaning challenge. Makeshift scaffolding attached (photo, hangar bay door partially open) allowed crewmen to scrub some of the areas with long handled brushes and Naval Aircraft Factory soap or Castile soap. The septic tank discharge also became part of the ship’s regular cleaning maintenance. Crewmen also noticed dust settling in spaces, and on girders, requiring periodic use of a vacuum cleaner. This prevented appreciable weight gain owing to dust accumulation on the horizontal longitudinals. A trap kept dust away from its fan, minimizing explosive potential. A gasoline tank had collapsed on the trip, filling the corridor with dangerous fumes for anxious hours; but sailors were cautioned never to use gas as a cleaning agent.

Images of the Akron when in California show a rather soiled appearance, with the soot from the engine exhausts presenting a cleaning challenge. Makeshift scaffolding attached (photo, hangar bay door partially open) allowed crewmen to scrub some of the areas with long handled brushes and Naval Aircraft Factory soap or Castile soap. The septic tank discharge also became part of the ship’s regular cleaning maintenance. Crewmen also noticed dust settling in spaces, and on girders, requiring periodic use of a vacuum cleaner. This prevented appreciable weight gain owing to dust accumulation on the horizontal longitudinals. A trap kept dust away from its fan, minimizing explosive potential. A gasoline tank had collapsed on the trip, filling the corridor with dangerous fumes for anxious hours; but sailors were cautioned never to use gas as a cleaning agent.

Leaving California on June 11th, Akron had to dump fuel and discharge her planes over Texas to again squeeze through the pass near Van Horn. She moored at Paris Island, South Carolina, for refueling, only then to have to defuel a couple tons, since no helium was available in South Carolina to top off the waterlogged airship. Safely docked on the 15th, Akron had been away from Lakehurst for thirty-eight days. Our DVD “The Flying Carriers” details Akron’s history and much of its source raw footage is included on the silent DVD “USS Akron.“

Leaving California on June 11th, Akron had to dump fuel and discharge her planes over Texas to again squeeze through the pass near Van Horn. She moored at Paris Island, South Carolina, for refueling, only then to have to defuel a couple tons, since no helium was available in South Carolina to top off the waterlogged airship. Safely docked on the 15th, Akron had been away from Lakehurst for thirty-eight days. Our DVD “The Flying Carriers” details Akron’s history and much of its source raw footage is included on the silent DVD “USS Akron.“

The ship’s electrical system is hardly mentioned in the literature, a testament to its design capacity and reliability. The generator room (photo), just aft of the galley on the starboard side, featured twin generators driven by 4-cylinder automobile-type engines. Intake scoops unique to the starboard side are visible, directing air up to the Model-A like radiators. (Note the voltage selector for the

The ship’s electrical system is hardly mentioned in the literature, a testament to its design capacity and reliability. The generator room (photo), just aft of the galley on the starboard side, featured twin generators driven by 4-cylinder automobile-type engines. Intake scoops unique to the starboard side are visible, directing air up to the Model-A like radiators. (Note the voltage selector for the

airplane engine starters.) The high voltage needed for the tube transmitters and receivers was also generated here. Many ship’s lights are somewhat visible in this longer-exposure photo whose negative was damaged; busy Bay VII’s windows are highlighted.

#3 wooden propeller had carried away during the return flight and was replaced with a Hamilton-Standard two-bladed steel propeller (as photographs show). Eventually all the wooden props gave way to 2-blade steel. The NAS Lakehurst engineers also addressed the high-maintenance G-Z water recovery units. Creating their improved Mark IV water recovery condensers, they firs t replaced #7 on the starboard side in July of 1932. Much easier to keep clean and thereby more efficient, Mark IV slightly bettered the one-to-one gasoline weight recovery. Replacements were worked into the schedule, with the starboard side showing all but #5 changed when Akron appeared at the Miami Air Races (photo).

t replaced #7 on the starboard side in July of 1932. Much easier to keep clean and thereby more efficient, Mark IV slightly bettered the one-to-one gasoline weight recovery. Replacements were worked into the schedule, with the starboard side showing all but #5 changed when Akron appeared at the Miami Air Races (photo).

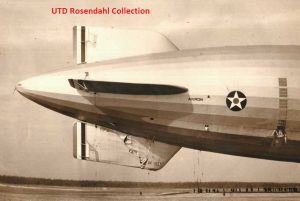

In an effort to increase speed the original factory very prominent bamboo-framed “bumper bag” (photo) was removed and reworked to about half the original depth. (The radio room’s window and its weighted, retractable antennas are seen above the crewman at the navigator’s drift gauge. Officer’s cabin windows are forward and also on the starboard side.) The accommodation ladder lead directly to the bridge floor level where another ladder lead up to the junction of the forward centerline passageway and main ring 170.

In an effort to increase speed the original factory very prominent bamboo-framed “bumper bag” (photo) was removed and reworked to about half the original depth. (The radio room’s window and its weighted, retractable antennas are seen above the crewman at the navigator’s drift gauge. Officer’s cabin windows are forward and also on the starboard side.) The accommodation ladder lead directly to the bridge floor level where another ladder lead up to the junction of the forward centerline passageway and main ring 170.

It was not unusual for Navy units to have a pet for a mascot. Akron adopted this hound and named him “Ronnie.” Rosendahl is standing under the panel that allows port & starboard, forward and aft mooring ropes to be dropped, just forward of the four engine telegraphs which each signaled two engine rooms.

It was not unusual for Navy units to have a pet for a mascot. Akron adopted this hound and named him “Ronnie.” Rosendahl is standing under the panel that allows port & starboard, forward and aft mooring ropes to be dropped, just forward of the four engine telegraphs which each signaled two engine rooms.

The ship’s officers sat for this portrait, their ceremonial swords resting on the fireproof bricks which can be seen here, paving Hangar #1’s deck.

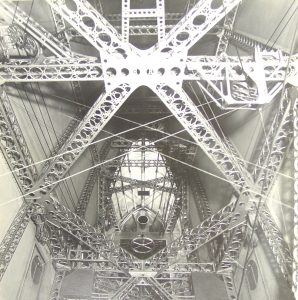

The Curtiss factory started delivering the Sparrowhawk production run in the summer of ’32. Primary  visible differences from the prototype XF9C-1 (top) were the raising of the upper wing, straight and taller rudder, and smaller wheels with low-pressure fatter tires. (The hook-on planes are detailed on their own page.) The last few of the six F9C-2 planes (below) were not received until September and the updated prototype was not delivered until the following January; four units were designated for the ZRS-5. It was discovered that girder structure in Bay VII conflicted with stowing the aft two airplanes on the X-shaped monorail truss. Added to the gripe list, a plan was drafted to hinge the conflicting girders, while the factory took note and modified ZRS-5 in the making.

visible differences from the prototype XF9C-1 (top) were the raising of the upper wing, straight and taller rudder, and smaller wheels with low-pressure fatter tires. (The hook-on planes are detailed on their own page.) The last few of the six F9C-2 planes (below) were not received until September and the updated prototype was not delivered until the following January; four units were designated for the ZRS-5. It was discovered that girder structure in Bay VII conflicted with stowing the aft two airplanes on the X-shaped monorail truss. Added to the gripe list, a plan was drafted to hinge the conflicting girders, while the factory took note and modified ZRS-5 in the making.

Helium integrity being paramount, cell inspections for holes and chafing were part of the keel watchstander’s routine. Seeming thick in photos pressing against their ramie cord netting, the cells were sheer, about like what one would expect from sticking scotch tape on either side of a handkerchief. They were about the color of khaki uniforms. Ramie cord netting, placed to spread the load between the fragile cell to the hard structure, turned out to be a bit on the large side, sometimes allowing bulge-through as seen in this photo in one of the side keel passageways. The netting frequently broke and had to be repaired. On each main ring the elastic bulkheads designed to prevent surging between bays were managed by shock-absorber-like resiliency devices visible in this cell test during construction (arrow).

Helium integrity being paramount, cell inspections for holes and chafing were part of the keel watchstander’s routine. Seeming thick in photos pressing against their ramie cord netting, the cells were sheer, about like what one would expect from sticking scotch tape on either side of a handkerchief. They were about the color of khaki uniforms. Ramie cord netting, placed to spread the load between the fragile cell to the hard structure, turned out to be a bit on the large side, sometimes allowing bulge-through as seen in this photo in one of the side keel passageways. The netting frequently broke and had to be repaired. On each main ring the elastic bulkheads designed to prevent surging between bays were managed by shock-absorber-like resiliency devices visible in this cell test during construction (arrow).  They were no easy reach and had to be kept greased. The crew came to watch the upper six devices in each bay most carefully. Gas purity checks were made every week and recorded; samples, taken close to the cell equator, were taken to the station helium plant for the analysis. A daily fullness report was eventually reduced to comparison to a standard 29.92 inch barometer at 32 degrees F. Records on helium uptake were kept, and a monthly total helium report was made to BuAer. Logs were kept on each cell, with attention paid to location of cells and spares in the station’s environmentally friendly cell storage room, equipped with very long racks.

They were no easy reach and had to be kept greased. The crew came to watch the upper six devices in each bay most carefully. Gas purity checks were made every week and recorded; samples, taken close to the cell equator, were taken to the station helium plant for the analysis. A daily fullness report was eventually reduced to comparison to a standard 29.92 inch barometer at 32 degrees F. Records on helium uptake were kept, and a monthly total helium report was made to BuAer. Logs were kept on each cell, with attention paid to location of cells and spares in the station’s environmentally friendly cell storage room, equipped with very long racks.

Since there could never be enough helium to waste, Akron’s cells were topped off to a level based on the necessary expansion reaching the projected operating altitude for the forthcoming mission, tempered by environmental factors. Temperature complicated the lift calculation, since a 5 degree F temperate change would change the cell volume by 1%, and normal variation of minus 3 to plus 10 degrees F was noted. (Much wilder swings were recorded.) Moisture in the ship and humidity in the air had to be accounted for, usually about a ton of lift was lost in typical Lakehurst humidity. Lifting off, the cells would expand about 1% per cent of their volume for each 330 feet of altitude gained. Since 1% of Akron’s gas volume was roughly 4000 pounds of lift, a balance to conserve precious helium was struck by keeping operating altitudes low, and taking on airplanes later on after their weight could be carried dynamically. Run up to 50 knots, Akron could carry more than ten extra tons.

It was assumed cell repairs would have to be made in flight, and cell repair kits with patches and glue were stowed at strategic locations. Likewise, shoring kits made of lumber with rounds to match the girder hole spacing were also carried. Eventually a complete replacement control cable, matching the length of the longest aboard and terminated at one end, was also carried, allowing a broken control cable to be quickly sized, terminated and installed in flight. Inspected during and after each flight, “the 8 X 19 flexible cable used [aboard] gave excellent service and was kept sluiced down with Navy standard grease for flexible cable, all surplus grease being wiped off before flight.”

It was assumed cell repairs would have to be made in flight, and cell repair kits with patches and glue were stowed at strategic locations. Likewise, shoring kits made of lumber with rounds to match the girder hole spacing were also carried. Eventually a complete replacement control cable, matching the length of the longest aboard and terminated at one end, was also carried, allowing a broken control cable to be quickly sized, terminated and installed in flight. Inspected during and after each flight, “the 8 X 19 flexible cable used [aboard] gave excellent service and was kept sluiced down with Navy standard grease for flexible cable, all surplus grease being wiped off before flight.”

Crewmen were required to wear soft-soled shoes or sneakers. This photo of the enlisted bunk space, port side Bay VII, shows a floor register. Air, heated across the exhaust manifold of #8 engine, was ducted forward, including the bow cabins. Instructions were to avoid using the diagonal girders for support when climbing in the main rings. Weight was to be applied to the girder’s corners, never the center webbing. When necessary to use lightening holes to climb, weight was to be spread between hand and footholds. When climbing longitudinals, crewmen were told to step on the outer or inner edges, never the center trusses. The intermediate girders’ holes were not to be used as footholds and they were not be climbed on above the keels.

Crewmen were required to wear soft-soled shoes or sneakers. This photo of the enlisted bunk space, port side Bay VII, shows a floor register. Air, heated across the exhaust manifold of #8 engine, was ducted forward, including the bow cabins. Instructions were to avoid using the diagonal girders for support when climbing in the main rings. Weight was to be applied to the girder’s corners, never the center webbing. When necessary to use lightening holes to climb, weight was to be spread between hand and footholds. When climbing longitudinals, crewmen were told to step on the outer or inner edges, never the center trusses. The intermediate girders’ holes were not to be used as footholds and they were not be climbed on above the keels.

In this image, Graf Zeppelin uses the Navy’s Class “B” base to replenish at Opa-Locka, Florida, on his way up from South America. Also called “expeditionary” bases, they could be constructed within a few square miles of low-obstacle terrain in which a 700-foot radius circle had been cleared and leveled. A railroad track circle for the stern carriage surrounded the stub mast whose winch could pull 24,000 pounds at 200 fpm. Ideally, a million cubic feet of helium was to be stored along with 20,000 pounds of gasoline. 6,000 gallons of ballast and drinking water was to be available, along with “a limited supply of consumables.” Barracks, mess hall and wardrooms were on the wish list as well. With one of these mast bases set up on the south end of Cuba, it was known getting helium beyond a rail head would be a challenge there – or anywhere overseas. A filled helium cylinder weighed about 125 pounds and it took eight and a half cylinders to deliver 1,000 cubic feet. Just that bank of bottles would occupy almost 21 cubic feet in an ocean vessel’s cargo hold. Moving a significant amount of helium overseas was never accomplished even at the height of WWII. Small wonder the Akron’s Captain passed on the opportunity to moor at Guantanamo Bay. He used the excuse they’d had a report of bad gasoline there, but RADM Moffett was not pleased.

In this image, Graf Zeppelin uses the Navy’s Class “B” base to replenish at Opa-Locka, Florida, on his way up from South America. Also called “expeditionary” bases, they could be constructed within a few square miles of low-obstacle terrain in which a 700-foot radius circle had been cleared and leveled. A railroad track circle for the stern carriage surrounded the stub mast whose winch could pull 24,000 pounds at 200 fpm. Ideally, a million cubic feet of helium was to be stored along with 20,000 pounds of gasoline. 6,000 gallons of ballast and drinking water was to be available, along with “a limited supply of consumables.” Barracks, mess hall and wardrooms were on the wish list as well. With one of these mast bases set up on the south end of Cuba, it was known getting helium beyond a rail head would be a challenge there – or anywhere overseas. A filled helium cylinder weighed about 125 pounds and it took eight and a half cylinders to deliver 1,000 cubic feet. Just that bank of bottles would occupy almost 21 cubic feet in an ocean vessel’s cargo hold. Moving a significant amount of helium overseas was never accomplished even at the height of WWII. Small wonder the Akron’s Captain passed on the opportunity to moor at Guantanamo Bay. He used the excuse they’d had a report of bad gasoline there, but RADM Moffett was not pleased.

There were many other lessons to be learned as USS Akron came of age. With her Mark IV condensers, smaller bumper and scrubbed exterior Akron somehow became less interesting to photogs in general and motion picture cameras in particular, with no footage of this modern appearance (photo below) known to us.

Read on to The USS Akron Matures

or

Back to ZRS-4 Evolves